Childe Hassam, a proud Yankee and native of Dorchester, Massachusetts, began his life in art in Boston. He trained first in his hometown, and then in Paris. By 1887, Hassam was exhibiting at the Paris Salon and working in an impressionist-influenced manner. As with most of the Americans who worked in the impressionist idiom, Hassam adapted the style to his own purposes, exploring the effect of brilliant light on color, without the dissolution of form pursued by some of the French Impressionist artists.

For Hassam, who had already made his mark as a professional artist in Boston, this period in France was a time of intense work, an opportunity, in the art capital of the world, to consolidate all that he had learned before, to hone his skills, and to incorporate French Impressionism into his own artistic idiom. Hassam enrolled at the Académie Julian, studying figure painting with Gustave-Rodolphe Boulanger and Jules-Joseph Lefébvre. He leased a studio at 11, boulevard Clichy, and made the streets of Paris his subject matter. In 1887 and 1888, he exhibited at the Paris Salon, and in 1888 at the Internationalen Kunstaustellung in Munich, Germany. In June 1889, he was awarded a bronze medal at the Exposition Universelle in Paris.

Hassam’s star rose quickly. He exhibited widely and won prestigious awards and medals. In 1889, he returned to the United States and established himself in New York City, where he soon became a focal point of the New York art scene, a founder of the New York Watercolor Club, and an active member of the Society of Painters in Pastel, the Society of American Artists, and The Players Club. Throughout the 1890s, Hassam continued to be vocal, visible, and a magnet for awards and honors. In 1893, he showed watercolors and won a prize for painting at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. In 1894, his illustrations illuminated the pages of An Island Garden, a memoir by his friend Celia Thaxter, the mistress of Appledore on the Isle of Shoals off the coast of New Hampshire.

In February 1896, a two-day auction of over two hundred paintings, watercolors, and pastels from Hassam’s studio was held in New York at the American Art Galleries. This sale prepared the way in late 1896 for Hassam to leave New York and return once again to Europe for an extended stay. Traveling first to Italy, he progressed north to France where, in 1897 and 1898, he worked extensively in both Paris and the province of Brittany. Like many American painters in the late 19th century, he was attracted to the picturesque village of Pont-Aven, where he painted a series of canvases depicting the rustic life of local peasants. Many of these paintings reveal Hassam’s new concern with artistic issues related to Post-Impressionism. Hassam’s palette assumed greater vibrancy and his brushwork became bolder. His stylistic evolution is also in evidence in the many canvases executed by the artist in Paris in 1897–98, such as his brilliant Pont Royale, Paris (Cincinnati Art Museum, Ohio), and Tuileries Gardens (The High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia). In both of these works, Hassam utilizes pigment in a new and expressive fashion which emphasizes the two-dimensionality of the picture surface.

In 1898, Hassam, unhappy about the unattractive jumble that characterized New York exhibition opportunities, joined with nine fellow American artists in a group calling itself simply “Ten American Painters.” Together with John Henry Twachtman (until his death in 1902), J. Alden Weir, Frank Weston Benson, Joseph Rodfer DeCamp, Thomas Wilmer Dewing, Willard Leroy Metcalf, Robert Reid, Edward Emerson Simmons, Edmund Charles Tarbell, and, from 1903, William Merritt Chase, Hassam showed paintings annually through 1918 in exhibitions designed and organized by the artists of the group.

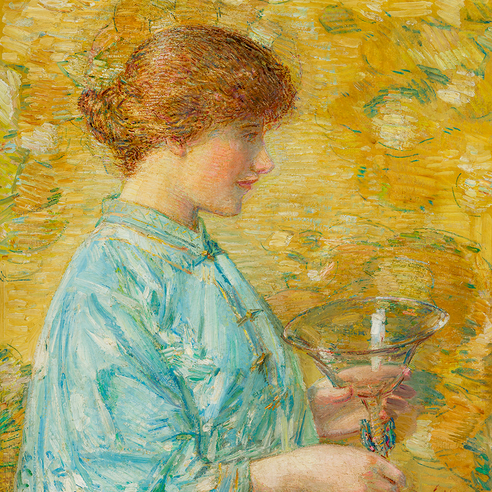

Hassam took his last trip to Europe in 1910, essentially recapitulating the itinerary of his 1897 sojourn, with the exception of Italy. Upon his return to New York, he took a new interest in painting the female form. The most famous result of this is his New York Window series, a highly decorative group of pictures of women set in diaphanously lit interiors.

Throughout his lifetime Childe Hassam rejected the “impressionist” label, placing himself, instead, in the lineage of English landscape tradition descending through James Mallord William Turner and John Constable. Indeed, Hassam’s mature work is typically American in that it is stylistically inconsistent—freely combining strategies, devices, and influences in an eclectic mix to suit the artist’s immediate purpose.