The foremost American still-life painter of the late 19th century, William Michael Harnett was a trompe l’oeil specialist, applying his distinctive brand of deceptive illusionism to carefully composed arrangements of dead game, printed matter, domestic bric-a-brac, and objects associated with the enjoyment of music, literature, and art. In contrast to his mid-century predecessors, whose opulent still lifes of fruit and flowers reflected a mood of optimism and a sense of abundance, Harnett’s compositions are highly pensive in tone, exuding a sense of quiet introspection and inviting the viewer to ponder such notions as solitude and the inevitable passage of time. During his day, his oils were acquired by cultivated art aficionados such as Thomas B. Clarke and George Hearn, but the majority of Harnett’s patrons were affluent businessmen, manufacturers, brewers, and merchants who were drawn to his male-oriented motifs and his “fool-the-eye” realism. His meticulously rendered paintings were more likely to be found in bars, department stores, pool halls, and drugstores than in the formal parlors of leading tastemakers, who favored academic figure paintings and genre scenes or the more expressive landscapes associated with the Barbizon School and Impressionism.

Although critics of the 1880s and 1890s admired Harnett’s flawless technique and his gifts as a colorist, he received little attention from the art press, who failed to appreciate his penchant for abstract pattern and the underlying symbolism of his work. Following his death, his pictorial legacy was largely forgotten until Edith Gregor Halpert, the proprietor of the Downtown Gallery in New York’s Greenwich Village, began exhibiting his work during the late 1930s, at a time when the sharp-focused realism of painters such as Luigi Lucioni and Peter Blume had become increasingly popular. As Halpert put it, Harnett’s still lifes provided a “link between Dutch art of the seventeenth century and sur-realism [sic] of the twentieth” (Edith Gregor Halpert, “Nature-vivre” by William M. Harnett, exhib. cat. [New York: Downtown Gallery, 1939], n.p.). As a consequence of Halpert’s efforts, Harnett was among the few nineteenth-century artists represented in the groundbreaking exhibition, American Realists and Magic Realists, held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1943. The rediscovery of Harnett culminated a decade later with the publication of Alfred V. Frankenstein’s seminal study, After the Hunt: William Harnett and Other Still life Painters (1953; rev. ed. 1969), which underscored his important role in establishing a taste for illusionistic still life painting in Gilded Age America and brought his work to the attention of a new generation of collectors. In addition to analyzing his stylistic evolution and compiling a critical catalogue of extant work, Frankenstein separated Harnett’s paintings from a number of forged and misattributed oils that were executed by his friend and colleague, John Frederick Peto.

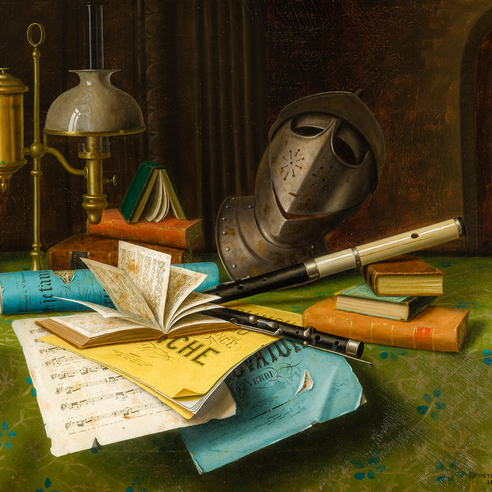

Born in Clonakilty, County Cork, Ireland, Harnett was raised in Philadelphia, where, as a young man, he learned to engrave metal and studied painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. In 1869, he moved to New York, working as an engraver for prestigious firms such as Tiffany & Company and attending evening classes at the National Academy of Design and the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art. Returning to Philadelphia in 1876, he gave up engraving and resumed his training at the Pennsylvania Academy, developing a style characterized by precisely delineated forms, warm colors, and closely-cropped designs. He initially painted renditions of fruits and vegetables but by about 1877 he was exploring more innovative themes involving combinations of humble, everyday objects such as beer steins, pipes, books, stationery, and newspapers. He also painted the occasional rack picture, as well as depictions of currency.

In 1880––having enjoyed steady sales of his work in Philadelphia––Harnett traveled to Europe, visiting London and Frankfurt before settling in Munich in early 1881. While his American cohorts were exploring the painterly manner associated with Munich realism, Harnett studied the work of the Old Masters (including Dutch still-life paintings of the seventeenth century) and continued to focus on aesthetic clarity, imbuing his oils with an even greater degree of exactitude and finesse while turning his attention to more elaborate compositions. As a result of this cosmopolitan experience, Harnett also began acquiring and incorporating Old World antiques into his paintings, depicting them against fine draperies or oriental rugs set on marble or wooden tabletops, often against a paneled backdrop. He remained in Germany until early 1885, when he went to Paris, spending the spring and summer there before settling in New York.

Harnett continued to paint illusionistic still lifes until about 1889, when his health began to deteriorate and his painting output decreased considerably. He died at New York Hospital on October 29, 1892, after which a memorial exhibition of his work was held at Earle’s Galleries in Philadelphia. The centennial of his death was commemorated by a major retrospective exhibition organized by the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, in 1992.