In 1920, Hunt Diederich recalled an early memory: “As a child of five I embarked upon my artistic career by cutting out silhouettes of animals with a pair of broken-pointed scissors....” What began as child’s play remained a constant in Diederich’s life, an essential element of his creative process in his years as a professional artist.

The urge to cut paper into decorative or narrative shapes and attach it to a contrasting background appears to be nearly universal among cultures with paper technology. The technique has been documented as early as first-century China. Straddling definition between art and craft, the process has different names in different languages—Wycinanki in Poland, Mon-Kiri in Japan, Decouper in France and Scherenschnitte in German-speaking Europe. The craft migrated to colonial America with immigrants from Germany and Switzerland who settled in Pennsylvania and became popularly known as the Pennsylvania Dutch.

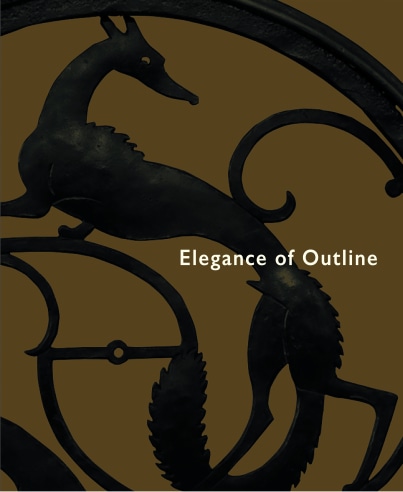

Diederich’s own devotion to paper cutting continued throughout his career. The paper cutouts proved to be closely related to his wrought-iron works. Because the two-dimensional, silhouetted, design-oriented aesthetic was identical in both mediums, the artist found he could experiment with forms in paper first, then easily transfer them to the more robust medium. This is not to imply the silhouettes were merely studies; they were indeed finished works. Both mediums conveyed the same fluidity and spontaneity, and thus were appreciated for the same reasons. The wrought-iron and silhouettes are simply two very different mediums with a shared aesthetic, making them inextricably entwined within the artist’s oeuvre.

Diederich’s paper cutouts capture the distinctive sense of animation and vitality so specific to his art. They are elaborate, fragile, and cut with startling precision, transforming the simplest of mediums into works of great complexity. The forms are carefully attenuated and generalized, yet close inspection reveals an astounding degree of detail, leaving the viewer in awe of the skill and patience on display. In the cutouts Diederich could explore the subtleties of the interplay of figure and ground, solid and line, as expressed in the forms of his beloved animals. These musings were applicable then to the various media in which he worked. And, in a peripatetic life, with young children underfoot, cutouts were portable and always accessible. As his daughter Diana Diederich recalled: “I think that childhood enthusiasm is something we can trace through much of his work later,—an interest in silhouettes, a fascination with empty space, the balance of positive and negative space.”

Cutouts were a constant in Diederich’a life, the first stirring of his aspirations to art, a visceral recollection of a time when he was a child, when the world was a known and secure place and when, whenever he needed them, animals were his for the conjuring.