Louisa Chase (1951-2016) was a questing spirit, writing in 1979 that “painting for me is a constant search to hold a feeling tangible.” From her Symbolist iconography of the late-1970s through the gestural abstractions of the mid-1980s and beyond, that search never left her. Chase looked inward for her subject matter, imbuing the resulting work with the force of the artist herself as she wrestled with desire, ambition, frustration, depression, happiness, and fear. Hirschl & Adler Modern is pleased to present Force Field, the artist’s first solo exhibition with H&A and her first solo show in New York City in over twenty years. Covering three decades through more than 20 paintings, prints and drawings, Force Field is a testament to how successful Chase was in her search.

Force Field presents all phases of Chase’s oeuvre without a chronological hierarchy. She employed a variety of approaches at different times, so that, despite having attracted a number of labels, among them “new image school,” and “neo expressionist,” there is not one distinctive “Chase style.” Untitled, about 1978, vibrantly red with thickly applied paint, showcases the imagery and paint handling that won Chase such early acclaim. Almost sculpted with paint, a large “nail” shape dominates the picture as it hovers and radiates its energy across the painting while a smaller nail is piercing an undulating grid done in lines of rich impasto. Chase fused her signifiers of art making, like nails and the grid, with the pure materiality of paint to create an arresting composition at a time when painting was reasserting its dominance.

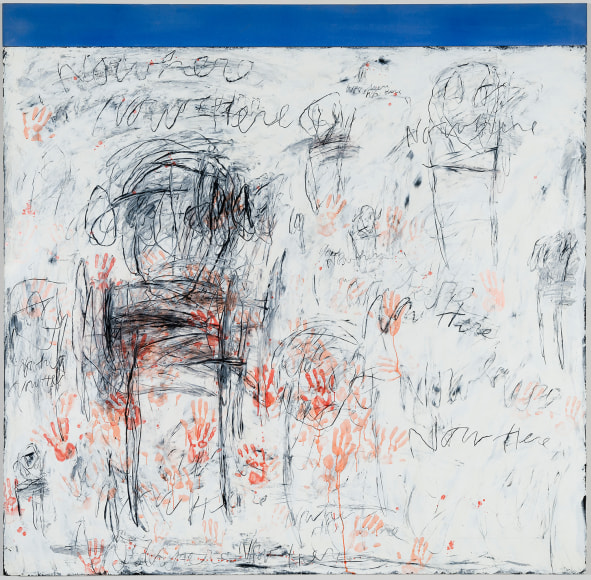

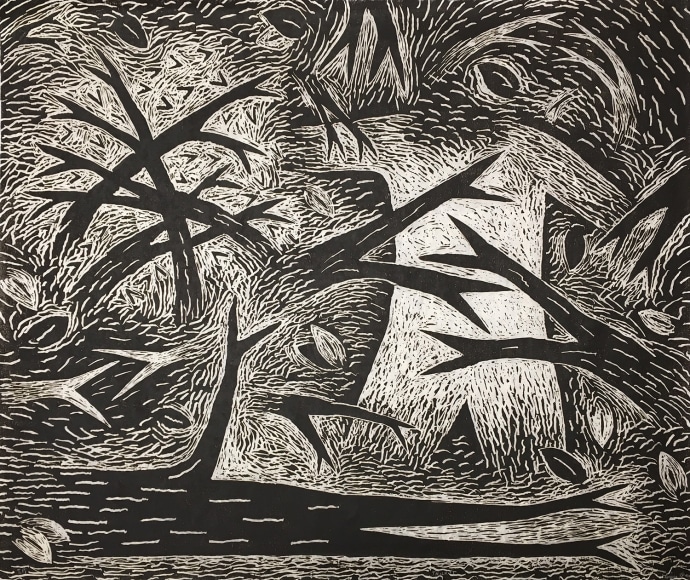

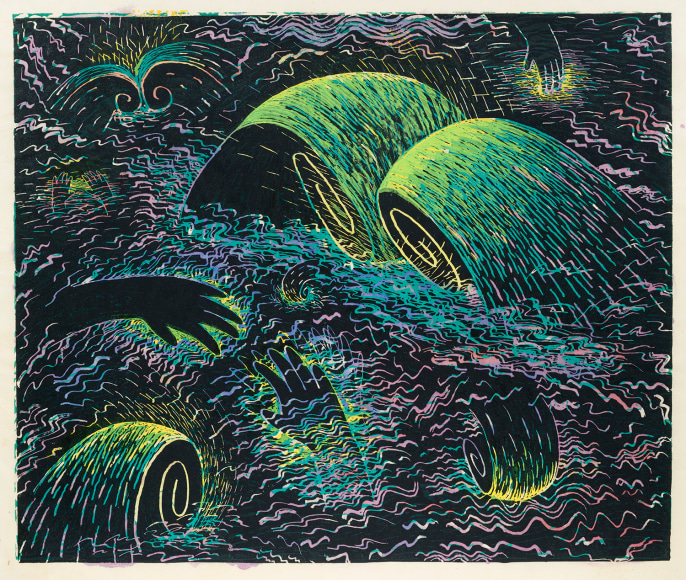

Paintings like Sunset Grip, 1983, show Chase not only “holding a feeling” but making it beautiful. Arms and hands embrace themselves in a lush pink sky as an electric sunset unfolds, radiating warmth and optimism. Despite the density of the paint and mark-making, the painting feels light and open – a duality that the artist worked hard to achieve. Perhaps born out of her deep printmaking experience, Chase emphasized her mark-making by scratching into the surface of the paint as it dried. This emphasis on the mark and on the gesture increased overtime and, by the mid-80s, it was the driving factor in her work. Not able to completely abandon her imagery, Chase now buried it in a vortex of scratches along with words embedded in a stream of conscious gesture, as in Nowhere, Now Here, 1986-87. Bodies and heads float in and out of a creamy white ground while the words “nowhere” and “now here” surround them, all expressionistically carved into the paint itself. Chase, who struggled throughout her life maintaining close relationships because of issues like depression and alcohol abuse, wrangled the gesture, imagery and text into an abstraction that feels universal in its declaration of existence. Whereas she may have felt as if she was nowhere, she was affirmatively Now Here.

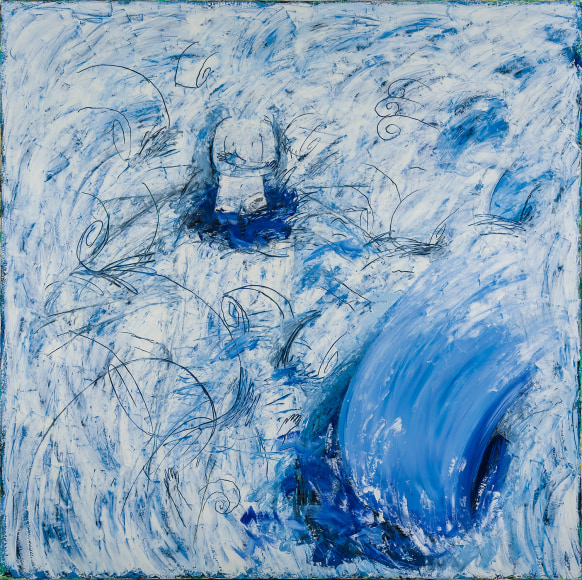

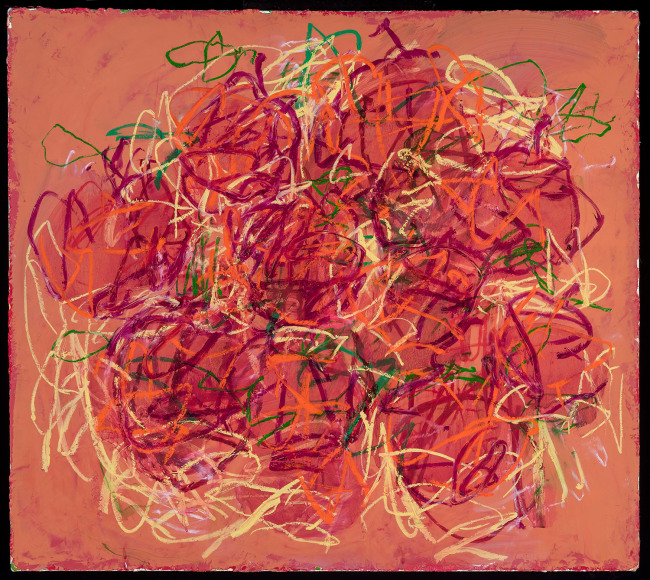

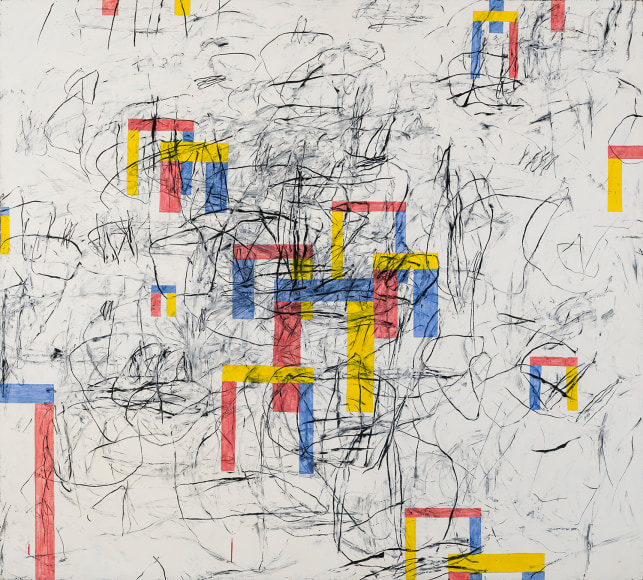

A more unified composition of mark and shape became Chase’s focus through the 1990s and by the early 2000s she had arrived at it. Gone by now is the reliance on incision to the painting’s surface as Chase had come full circle, pursuing a build-up of paint and gesture like the work of the mid- to late 70s. Works like Untitled (Bowl of Cherries), about 2003, and Buddha, 2011, best illustrate Chase’s late work. Dense rhythms of gestural line, recalling and employing automatic writing, move in and out of solid shapes and symbols done in high-key color. These later paintings are vibrant, glowing with an energy that belied the artist’s own deteriorating health and spirits.

Force Field lays bare Louisa Chase’s ferocity and intensity in life and in her art. Chase was unable to separate the two and her career was spent reconciling them. That pursuit generated a remarkable body of work. While Chase’s struggles were uniquely personal, the paintings, drawings and prints she made are generously universal. Her work continues to startle and to engage with a force all her own.