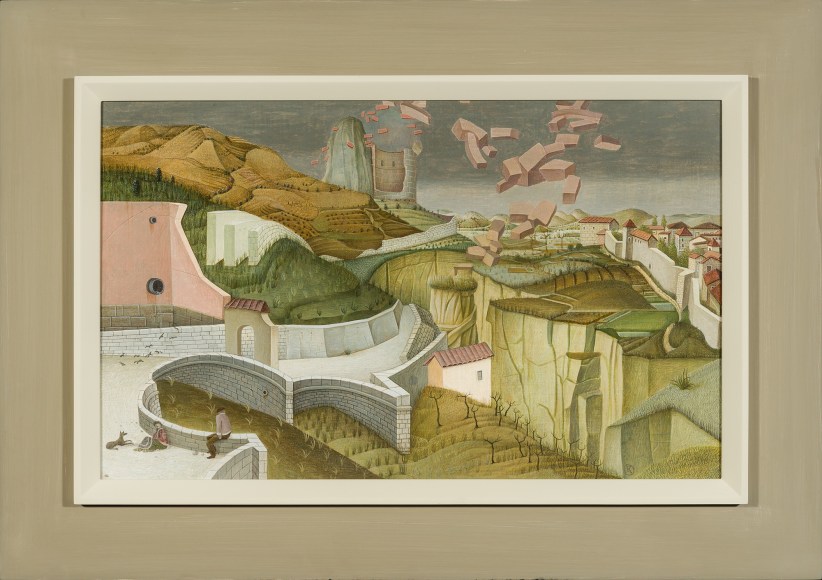

JULES KIRSCHENBAUM (1930–2000)

Destruction of Babel, 1956

Tempera on canvas on Masonite, 15 x 24 in.

Monogrammed (at lower right): K [circled]

RECORDED: Thomas Worthen, Jules Kirschenbaum: The Need to Dream of Some Transcendent Meaning (Iowa City: University of Iowa Museum of Art, 2006), p. 17 no. 34 illus.in color

EXHIBITED: Huguenot Festival of the Arts, Pelham, New York, April 1961

EX COLL.: the artist; [Harry Salpeter Gallery, New York]; Museum of Modern Art, New York, Art Lending Service, by 1961; to the artist’s sister, Beverly Goldstein, New York, around 1963, and descent until the present

The Old Testament description of the Tower of Babel, related in the Book of Genesis, Chapter 11, verses 1 through 9, is one of the foundational stories of the Judeo-Christian tradition. More than that, variations on its theme appear in multiple ancient cultures including Sumerian and Assyrian, Greco- Roman, and in origin stories found in peoples as geographically separated as Arizona, Nepal, Botswana, and the Admiralty Islands. Clearly the story answers a basic human question: how is it that sharing one planet and basic physical features, we humans speak so many different and mutually unintelligible languages? Equally clear is the moral thrust of all these traditions: the disastrous consequence of human hubris in the context of divine power.

The subject of the Destruction of Babel appealed to Jules Kirschenbaum on many levels It is possible that the young artist, a declared lover of Northern Renaissance painting, saw one or both of Pieter Breugel the Elder’s depictions of the Tower (one in Rotterdam, the other in Vienna) during his European travel in the summer of 1951. He would not have had to see Breugel’s work, however, to know the story. Growing up in a culturally Jewish family in The Bronx, the Biblical account of the Tower of Babel would have been part of the fabric of his childhood.

Kirschenbaum's Babel appears to have only three inhabitants: a man, sitting on a wall and looking in the direction of bricks fluttering down from the sky, a woman, slumped against the inside of the wall and facing away from the destruction, and a dog resting on the ground. The destruction of the Tower elicits not concern, but an idle curiosity. The falling bricks that drift down are three dimensional but appear as weightless as paper. A small flock of birds flutter near the family, highlighted against the low wall and the pathway, wisely avoiding the sky.