ROBERT NATKIN (1930–2010)

Described as the “author of a dappled infinite,” Robert Natkin created some of the most innovative color abstractions of the late twentieth century (Carter Ratcliff, “The Dappled Infinite,” Art & Antiques 38 [December 2015]). Populated by stripes, dots, grids, and an array of free-floating forms, his lightfilled canvases are sensuous, playful, and visually complex, representing “a unique formal universe of unparalleled beauty” (Louis A. Zona, “Foreword: Robert Natkin: Crescendos of Whispers,” in Robert

Natkin: A Retrospective: 1952–1996, exhib. cat. [Youngstown, Ohio: Butler Institute of American Art, 1997]).

Born in Chicago, Natkin was the son of Russian-Jewish immigrant parents who worked in the garment industry. At age five, he began going to the movies (often six times a week), an activity that, in addition to providing him with a measure of respite from his dysfunctional family, would later influence his work as a painter. In 1945, Natkin’s family moved briefly to Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where Natkin decided to pursue a career as an artist. A natural draftsman, he initially wanted to become an illustrator, like Norman Rockwell, whose work he’d seen in the Saturday Evening Post. However, while attending the school of the Art Institute of Chicago from 1948 to 1952, Natkin was afforded the opportunity to study the museum’s world-class collection of French post-impressionist art and decided to turn his attention to painting instead. During these formative years, Natkin was inspired by the examples of Pierre Bonnard and Henri Matisse, who used decorative patterning and arbitrary color to evoke mood. Most importantly, he also discovered the work of Paul Klee, the SwissGerman artist whose whimsical, semi-abstract paintings reflected his belief that “art does not reproduce the visible but makes visible”––a credo that nurtured Natkin’s burgeoning interest in emotional content. As a student, Natkin was also a frequent visitor to the Field Museum of Natural History, where he was attracted to the stylized shapes of American Indian art and Peruvian textiles.

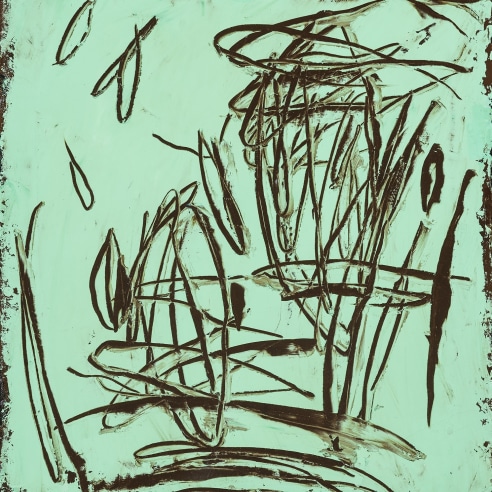

An article on Abstract Expressionism, published in Life magazine in 1949, was equally vital in determining Natkin’s evolution as a painter. In 1952, he lived briefly in New York, where he saw and was influenced by the bold canvases of Willem de Kooning. Following this, Natkin spent a few months in San Francisco before returning to Chicago, where he worked at the Newberry Library while painting in his spare time. He initially focused on portraits and expressionist figure pieces, but by 1954–55 he was producing his earliest abstract work and fraternizing with a group of artists that included the painter Judith Dolnick (b. 1934), who he married in 1957. During that same year, Natkin and Dolnick established the Wells Street Gallery in a dilapidated storefront in Chicago’s Old Town, where they exhibited their own work as well as that of other progressive-minded local artists, among them the sculptor John Chamberlain and the photographer Aaron Siskind, as well as painters from New York, including de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko. Although Natkin never embraced the concept of “action painting” as exemplified in the work of Pollock, he did, for a time, explore de Kooning’s agitated, gestural brushwork, as apparent in canvases such as Keep It Quiet (1957; private collection, formerly Hirschl & Adler Galleries, New York). (For Natkin’s Chicago period, see Robert Natkin in Chicago: The 1950s, exhib. cat. [Chicago: McCormick Gallery, 2015]).

In 1959, aware of the limited patronage for abstract art in Chicago, Natkin and Dolnick moved to New York, where Natkin joined the stable of artists associated with the Poindexter Gallery, known for its support of emerging painters and sculptors. On the occasion of his début exhibition at Elinor F. Poindexter’s gallery in late 1959, the critic Dore Ashton praised the “bright, experimental boldness” of Natkin’s paintings and observed that he “obviously enjoys attacking a large canvas, filling its field with many forms and many colors, making them glide and slip, before and behind, each other” (“Natkin’s Avant-Garde Paintings on View,” New York Times, January 7, 1960). Natkin’s reputation in Manhattan art circles was further enhanced when he was included in the exhibition, Americans Under 35, held at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1960.

Immersed in the dynamism of the New York art world, where Abstract Expressionism and Color-Field painting were the dominant styles of the day, Natkin’s aesthetic approach continued to evolve. In 1961, he adopted a serial approach to painting, a practice he would adhere to throughout his career. (For an overview of the salient characteristics of Natkin’s serial work, see Robert Natkin: A Retrospective: 1952–1996). In his earliest cycle, known as the Apollo series (which Natkin worked on intermittently into the early 1970s), he used vertical stripes of varying thicknesses and textures to suggest the interplay of color and light while creating a strong architectonic quality, as apparent in works such as Beatrice (1964; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra). During the mid-1960s––in response to the color theories of Josef Albers, contemporary jazz, and his admiration for Chicago architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Sullivan––Natkin retained the upright format of his Apollo paintings in his Straight Edge and Step canvases, imbuing them with a heightened sense of order and structure by using masking tape to create clearly defined areas of form and color.

Natkin embarked on his next thematic group, the Field Mouse series, in 1968. Based on Ezra Pound’s translation of a Chinese poem which dealt with the fleeting passage of time, the Field Mouse paintings represented a new stage in Natkin’s artistic evolution: moving away from the cool and contemplative approach of the Apollo works, he developed a more intricate style (indebted to Klee), depicting diamonds, polygons, ovals, squiggles and other shapes against textured, delicately toned backgrounds interspersed with seemingly randomly placed dots and daubs of pigment and areas of crosshatching, as in Between the Sapphire & The Sound Unfurls the Rose of Vision (1969; Harvard Art Museums,

Cambridge, Massachusetts). The inclusion of several of Natkin’s luminous canvases from the Field Mouse series in the exhibition, Timeless Paintings from the USA, held at Galerie Facchetti in Paris in 1968, was instrumental in bringing him to the attention of art aficionados in Europe.

In 1970, following a retrospective exhibition of his work at the San Francisco Museum of Art (now the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art), Natkin and his family relocated to West Redding, Connecticut. One year later, while serving as artist-in-residence at the Kalamazoo Art Center in Michigan, Natkin put aside his brushes and began to use sponges, soaked in acrylic paint and wrapped in pieces of cloth or netting, which he would apply to his support with different levels of pressure, a technique that enhanced the decorative quality of his paintings. The artist first applied this methodology to his Intimate Lighting series, which was influenced by an exhibition of cubist painting that he saw at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The year 1971 also marked a pivotal moment in Natkin’s career in that he had the first of many one-man shows at the venerable André Emmerich Gallery in New York.

In the ensuing years, Natkin continued to develop his repertory of cyclical paintings, reviving older themes, such as his Apollo pieces, while exploring new subjects, as in his Bath and Color Bath paintings, which were inspired by the light and architecture he encountered on a visit to Bath, England, in 1974. (The Bath paintings were executed in understated monochromatic tones, while the Color Bath paintings feature a range of soft-toned hues woven together to evoke a diaphanous curtain of light.) In 1977, following his retrospective exhibition at the Moore College of Art in Philadelphia a year earlier, Natkin visited the Paul Klee Foundation in Bern, Switzerland. Returning to America, he embarked on the Bern series, using rags and sponges (on both canvas and paper) to create spirited yet very intimate canvases featuring the geometric and biomorphic shapes of his earlier Field Mouse pictures, rendered now in strong, saturated primary colors, as well as black.

The Bern paintings were followed by the Hitchcock series, Natkin’s greatest and most engaging cycle in which he paid homage to the director, Alfred Hitchcock––a raconteur who, like Natkin, also used recurring themes and devices to express aspects of the human condition. As Leda Natkin Nelis has observed, her father had “long been a fan of Hitchcock’s films which, despite their entertaining surface plots, teem with darker undertones and contradictions. As the artist points out, the director succeeds, despite the playfulness of his films, to depict and romanticize man’s more somber side. Like Hitchcock, Natkin likes to interlock pleasure—and beauty––with mystery and paradox” (L.N.N. [Leda Natkin Nelis], “Bern & Hitchcock Series,” in Robert Natkin: A Retrospective: 1952–1966, n.p.).

Natkin began the Hitchcock series during the early 1980s and continued to explore the theme for the remainder of his career. (For the Hitchcock paintings, see Michael Dillon, intro., Robert Natkin: Recent Paintings from the Hitchcock Series, exhib. cat. [London: Gimpel Fils, 1988] and Peter Fuller, Robert Natkin: Recent Paintings from the Hitchcock Series, exhib. cat. [New York: Gimpel & Weitzenhoffer, 1984). Taking his cue from Hitchcock’s practice of synthesizing different story lines into a cohesive narrative, Natkin sought to imbue his Hitchcock canvases with carefully considered arrangements of shapes that, as Carter Ratcliff has observed, lead “the viewer from one point to the next and the next, until the work is fully seen . . . In the ‘Hitchcock’ paintings . . . his forms show a heretofore-unseen inclination to settle into configurations evoking rather specific urban settings. Or forms flatten into patterns suggestive of maps with strong inclinations of the proper path for the eye to follow” (Ratcliff, “The Dappled Infinite”). These qualities––as well as the vibrant chromaticism associated with the Hitchcock cycle––can be found in works such as Danae (1995), in which seemingly weightless forms merge, mingle, and intersect with one another to evoke a sensation of joyous exuberance. The Green One and Night Rumble (their whimsical titles reflecting the lingering impact of Klee’s provocative wordplay) likewise exemplify Natkin’s penchant for light, texture, pattern, and gorgeous, emotive color, as well as his ability to create improvisational works of art while retaining an underlying sense of form and structure.

In 1981, Natkin was the subject of a major monograph written by the British art critic Peter Fuller, an early champion of his work (see Peter Fuller, Robert Natkin [New York: Abbeville Press, 1981]). An inventive, energetic, and opinionated artist, Natkin also voiced his own thoughts about contemporary art, writing articles on painters ranging from Klee and Arshile Gorky to Jasper Johns and Franz Kline for journals such as Modern Painters.

The subject of numerous one-man shows in America, Europe, and Japan, as well as a participant in numerous group exhibitions devoted to late-twentieth-century painting (most recently, Expanding Boundaries: Lyrical Abstraction: Selections from the Permanent Collection, held at the Boca Raton Museum of Art in Florida in 2009), Natkin died in Danbury, Connecticut, on April 20, 2010. Examples of his work can be found in major public collections throughout the United States and abroad, including the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; and the Centre Pompidou, Paris. In addition to his paintings, Natkin also left behind a colossal, 20 x 42 foot mural, executed in 1992 for the lobby of 1211 Avenue of the Americas in New York’s Rockefeller Center.